I-70 Review

Writing and Art from the Middle and Beyond

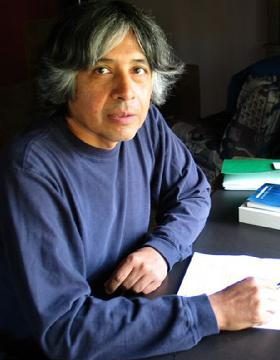

Andrés Rodríguez

Andrés Rodríguez is the author of a poetry collection Night Song (Tia Chucha Press) and a nonfiction work Book of the Heart: The Poetics, Letters, and Life of John Keats (Lindisfarne Press). His poems have appeared in Bilingual Review, The Cortland Review, Drunken Boat, Harvard Review, Hubbub, New York Quarterly, Valparaiso Review, Palabra, and other journals. He has also been included in the anthologies Currents from the Dancing River (Harcourt Brace), Dream of a Word (Tia Chucha Press), New Chicano/Chicana Writing (University of Arizona Press), and Wild Song (University of Georgia Press). In 2007 Rodríguez won the Maureen Egan Writers Award in Poetry sponsored by Poets & Writers. He has an MA in Creative Writing from Stanford University and a PhD in Literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz. He lives in Kansas City.

Writing a Poem

Several years ago I went to New York where I saw pizza delivery boys on bikes in Midtown traffic. The scene had a familiarity—I mean apart from the everyday sight of delivery boys. These were Mexican and Central American youth: short in stature, dark-skinned, jet black hair. I watched them as I walked the streets for hours, feeling there was something more than what I witnessed—something happening to me that involved my memories, my history, my whole being. I didn't know then I wanted to preserve those boys in a poem, but months later while in Wyoming I found myself still living with that feeling of recognition and trying to describe them on paper.

With the first words, control was suspended. I was disinterested: “Let's see where this goes.” Yet the witness in me was trying hard to remember, recover, and even relive what had taken place. Word by word, I was inducted into a remembered and recreated field, both literal and nonliteral. In the process of writing the poem, neither excluded the other; each balanced the other, as curiosity is the complement to control. The poem was a scene described, but below or inside the surface reality there was an idea that existed before that day in New York, an idea that was searching for embodiment. It is the idea that we are immigrants to reality—a sort of Sufi idea to which my Mexican immigrant background gives some sort of sense.

I wasn't consciously thinking of this idea as I wrote. I believe it is part of my nervous system, memory hoard, heart lore, poetics, or imagination. When I saw those delivery boys I had the strongest sense that I was seeing the past as well as the present and the future. The experience that elicited this sense led me to write the poem which became a passion and a joy as well as a responsibility. I feel responsible for or to that passion and joy which is life itself, poetry itself. And so for me the act of writing is an emergence, a migration across times or terrains, and a trust in a scene, story, or sense that will deliver me to something familiar and new, here and elsewhere in the world.

The Killing Floor

That morning inside the Swift packinghouse

we went on the killing floor together,

grey smoky light and cold air in winter.

You pointed out meat hooks, crank, and conveyor belt,

sick with stoic manhood that weighed o you

like a blood mark from that frozen room.

Sawdust swept down and powdered your face

as I twitched across an elevated platform.

Stranded below me, you seemed small, childlike,

looking up the narrow tier abutted

by a tilting rail. I watched you, father,

withdrawing from everything outside you.

The roof shivered like a spine, pinching

the hollow above me as you passed from sight,

a slim moonbeam in the dark below.

A cold draft descended. Something else

floated down, moon-white, filial, silent,

and followed you to the tank house

dragging a carcass skewered with knives.

I called to it. Then it too passed,

the cross-marked fire door closing shut behind,

and the hollow of my voice

deep and knotty over the haunted floor.

I was no longer your fine child

but a bone or mineral in another body.

Throughout that dark place I heard

one door after another swing shut,

and you, moving outside, ask something

swallowed by the chaos of the wind,

then climbed down after the ringing silence

to cross over with you into this life.

Portal of a Dream

At dawn I see a shadow

crossing your face

below the blue repose

of skin. It is edgeless

like hummingbird wings

thrumming before they

zip through space.

Awoken by this flight

or my stare, your mouth

flutters open, eyes still

closed, and then words

crack through to tell me

where you've been.

“I was down by the sea.

A woman there had

three babies sleeping

inside her. I saw them

through her skin!

They clung to each

other tenderly, so

tenderly, each face

vivid with the future.

I helped the woman

into a rowboat to sail

on the waves alone.

As I watched from shore,

a storm was gathering

and everything got still

before it went dark.”

You fall silent, gazing

now at what was. Deep

within the quiet we hold

together, entangled

again, I dream my way

into your voice to find

that afternoon when

we danced across

the sun-drenched floor,

bare feet leaving pools

that fled once seen.

It hurt to face such

ordinary brightness,

such casual daytime

splendor, because I see

the end in all things

no matter how I try

to seine beauty's brief

sight. And here I am

again trying to live

into what I see.

Delicate slim toes.

Thick bony heels.

We danced till we saw

our faces peering back

from the wall mirror.

You said our children

would be a mixed circuitry

of blood, nerve, and bone.

Then we saw a face,

bred by the late day's

shifting hues, gaze

back at us from that

portal of glass,

luminous as the sea.

Though safe in the

mooring of arms,

I feel low rolling thunder,

wings in every corner,

shadows to come

while we sleep.

I resist myself,

the absence learned

by love. I want

to wake and see

her who I dreamed,

bright as sunlight,

sharing the room

and dawn. I learn

your face by touching

and look for the woman of life,

that unengendered mother,

wondering if I can

dream her

the long way home.

The Road

Alone at night

I'm pulling the dead

weight of my car

down a country road.

Snow in the fields

makes dim light

as I pull for miles,

my hands and feet

colder than the chain

tying me to my useless ride,

its tires, windows, body

ruined by repeated

blows of city life.

Along comes a solitary man

who snatches the chain

from my hands and

runs off with the car

that lifts like a kite.

I chase after him.

“Keep running,” he says,

looking back over his shoulder,

those encouraging or

belittling words

offered like tantalus.

Then another man appears.

I know him,

or remember him,

as if from a dream.

John places a ball

gently in my hands

that feels so good,

round and warm

as I turn it over and over.

Before my eyes it

changes color, shape

through dark miles of sky.

I look at it again:

a small bird, wings

folded, eyes open,

is cradled in my hands,

silent and wakeful,

about to sing.

Cicadas

Louder now, they weave their song

among the trees, grappled onto branches

where the wind never upends them,

where summer gathers fire day and night.

Like old pipers wheezing the same

crazed note between catches of breath,

they sit unreachable in their height

and drone that underground music

after seven or seventeen years,

raucous lords of the air and earth.

How do they sleep so long in darkness

beneath the surface noise of the earth?

How do they know it's time to rise up

in the hottest month of the year? What

do they see after those murky years

with tiny eyes like beads of pitch or tar?

It must be memory's old bright place,

the first desert, prairie, swamp, or wood,

where their voices came bubbling up

to terrify or tire creation's other forms.

A man on my block who worked nights

once shotgunned the trees outside his house

as if that would stop the buggy music.

But when the smoke cleared it arose at once,

and that man fell back, silent, still again,

drained by those agonizers of throatless song.

When I lie in my room, unable to sleep

or dream or breathe the pressured air,

the sound in my ear is a silence in my heart,

pincered, dusty white, and unkillable.

As a boy I'd see one fall from the sky,

wrapped with a hornet in a death-embrace.

They'd land in a blur on the sidewalk or grass

and a prolonged, horrid cry let loose—

not like any human voice I'd ever heard,

but still a screeching or beseeching

that arced the air with a zinc flash

whose cinders fell on everything.

I'd watch the brief struggle until

death arose with a king in his arms.

The sudden chill felt back then

comes now with a buzzing heard in

chicharras, whose slangy meaning

is electric cattle prods. Somewhere

a torturer enters a cell or brightly lit room

with one of these ravagers of burning steel.

Its blackened head sparks and crackles,

searing the genitals of a woman or man

whose suffering feeds the lords of death,

whose cries last a thousand thousand years.

North

This far north I don't expect to see them

weaving through Manhattan traffic,

night and snow descending. But the sight

of these delivery boys on old bikes,

pizza boxes balanced on a knee, makes me

understand how generations repeat,

how the unchanged changing migrations

from Michoacán, Puebla, Chiapas,

and jungles farther south are always seeking

havens that need but never value them.

It's all here this far north: the young future

grandfathers, and me the old grandson,

watching them squeegee clouds from steaming

manholes as they glide along Park Ave.

Even the ghost of my father is here,

standing dumbstruck on the deck of a transport

bound for war, the Statue of Liberty

a stark miniature goddess looking back

as iron waves close between them.

All here and claiming me. This far north

I hear the Atlantic embroider its shores,

whispers repeating like rusty chains, spokes

shedding flecks of light through the dark,

and voices ten feet away murmuring

in the tone of overheard captives,

in the cipher of people always on the run.

Few ever see them. They come and go like

clouds or windborne wings under the stars.

Fewer still speak to them, only offer a tip

the way a breeze lifts a bird before wings

chop the air again, nervous soul across

the solid wall of money that scrapes the sky.

Met Life. Aetna. Bank of America.

This far north, stuck to the underside

of our existence, these boys lace the streets,

a flurry of deliveries through Midtown,

and even this recalls workers in the fields

bringing food to the tables of America.

The past does not pass, and souls and bodies

hunger for more than earth. I come to

Bryant Park, where the statue of Benito Juárez

punches the dark with a shiny black fist

to throw a light on the street for his brothers

who slip the nets of the city nightly,

changing from wings to clouds and back.

Now in the oncoming headlights,

snowflakes slanting across the sharp air,

crusting heads, eyelashes, and knees,

they follow the running course of the streets,

emerging from the dark underside,

pursued, under the gun, but always on the job.