I-70 Review

Writing and Art from the Middle and Beyond

Featured Poet

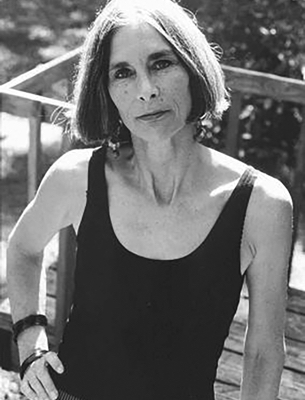

Lola Haskins

Lola Haskins' latest collection of poems, Like Zeros, Like Pearls is due in Spring 2025 from Charlotte Lit Press. Its predecessor, Homelight (Charlotte Lit, 2023), was named Poetry Book of the Year by Southern Literary Review. The one before that, Asylum (Pitt, 2019), was featured in the NYT Magazine and in The John Clare Journal. Past honors include two NEAs, the Iowa Poetry Prize, two Florida Book Awards, narrative poetry prizes from Southern Poetry Review and New England Review, a Florida's Eden prize for environmental writing, and the Emily Dickinson prize from Poetry Society of America.

Accidentals

Driving Thirteenth Street, I have the sense that something has moved since yesterday. The avenues as usual count down to Main, yet when I arrive at work, I find the turn has taken me half a block to the north.

In the elevator I push three instead of four. I spend the rest of the day compensating, leaning slightly to the right to allow for the unexplained weight on my left shoulder.

When the news came, we adjusted, says the family of the man who will not come home tonight. Yes, puts in his wife. We have schedules to keep. But sometimes I slip, and cook for four. And sometimes, when I go to serve, I find the food has gone, and all my pots are full of tears.

To Play Pianissimo

Does not mean silence,

the absence of moon in the day sky

for example.

Does not mean barely to speak,

the way a child's whisper

makes only warm air

on his mother's right ear.

To play pianissimo

is to carry sweet words

to the old woman in the last dark row

who cannot hear anything else,

and to lay them across her lap like a shawl.

Fortissimo

To play fortissimo

hold something back.

It is what the father does not say

that turns the son.

The fact that the summit cannot be seen

that drives the climber on.

Consider the graceless ones:

the painter who adds one more brush stroke.

the poet of least resistance

who writes past the end of his poem

Why Performers Wear Black

Because there is no black flower.

Because they are brides.

So that their hands can reach out of earth.

Because this is not practice.

Because they have agreed

not to talk with their mouths.

Because they know that sound

carries best at night,

the dip of feeding oars,

the loons' tremolo cry,

a whisper muffled in a woman's hair

on the far, dark, shore.

Four Small Portraits

Dragonfly

-Odonata aeshnidae

You were born breathing water.

Grown, you push your prey from the air

into the basket of your legs

o angel bright as grass

hovering above the red flowers.

Leafhopper

-Hemiptera fulgoriodea

Your husk is white with

black scatters

pale yellow at the tip.

If I could take you home

I would hold you to my ear

and listen for the sea.

Crickets, Vietnam

-Oecanthus fultoni

Snowy tree crickets

synchronize their songs

until leaf, branch, and core

are one repeating

tremble. When Yen

was asked

to define moonlight,

in pearl and dim blue

she painted this.

Katydid, Yucatán

-Meconmatina phrixa maya:

The calls of this species are inaudible to us.

Deep in the tangled bosque

a bright yellow leaf

calls out, over and over again.

Sometimes, tesoro, when

it's very late and we're lying

in our hammock, every bone

in my heart feels you dream.

A Short History of Iridescence

The apparent colors of the scarab are illusions created by the light changing

as it passes through layers of wing scales offset like randomly dropped cards.

Ancient Egyptians would place a scarab made of schist or jade on a gold chain over the

heart of a mummy, to speak for him when he reached the underworld.

*

Roman soldiers wore scarabs into battle as tokens of their masculinity.

*

For some early Christians, scarabs were symbolic of the Resurrection.

*

The Physiologus, a natural history written in the second century AD, describes the

scarab as made of excrement, living in filth, and carrying the stench of heresy.

*

In medieval Europe, a scarab placed inside a chest was thought to fill it with riches.

*

A wise man or woman will understand that, depending on the light, each of these is true.

The Spirituality of Cicadas

The Ancient Chinese believed they were spirits, because they consumed only dew

and by 4,000 years ago were placing their replicas on the tongues of the dead.

*

Two millennia later, “Slough off the Cicada's Golden Shell” appeared in Thirty-Six

Stratagems, along with “Kill with a Borrowed Knife” and “Befriend a Distant State

while Attacking a Neighbor.”

*

The Ancient Greeks believed they were humans transformed by the Gods and ate only air.

*

I believe that when my musician son is gone from here, he will teach himself their song.

Artist's Statement

I try to make each poem and each book its own world. I also try never to clone myself, and the reason I'm so happy in spite of the fact that I fail more often than I succeed is that I know that no matter how long I live, I'll never run out of things to learn, emotionally and intellectually, nor will I ever run out of beauty.

The Fruit Detective

On the table are traces of orange blood. There is also a straight mark, probably made by some kind of knife. The detective suspects that by now the orange has been sectioned, but there's always hope until you're sure. He takes samples. Valencia. This year's crop. Dum-de-dum-dum.

The detective puts out an APB. Someone with a grudge against fruit. He cruises the orchards. Nothing turns up except a few bruised individuals, probably died of falls.

A week passes. There are front page pictures of the orange. No one has seen it. They try putting up posters around town. Still nothing. The detective's phone rings. Yes, he says. And yes thanks, I'll be right over. Another orange. This time, they find the peel. It was brutally torn and tossed in a wastebasket. Probably never knew what hit it, says the detective, looking sadly at the remains.

There is a third killing and a fourth. People are keeping their oranges inside. There is fear about that with oranges off the street, the killer may turn to apples or bananas. The detective needs a breakthrough. He gets it. If you want to know who killed the oranges, says a muffled voice. Come to the phone booth at the corner of 4th and Market. Twenty minutes, it adds.

The detective hurries on his coat. When he gets to the booth,the phone is already ringing. It is the egg. I did it, says the egg, and Ill do it again. The detective is not surprised. No one but the egg could have been so hard-boiled.

A tenantless shell, rinsed,

makes a spoon

for the delicate soup of the sea.

In the Stark Lands

there are no trees to slow the wind.

Creatures underground come out only

with the stars. There are no other lights.

The distance to the horizon is a fierce

happiness. This is a portrait of my heart.

Below High Bradley

I cross a tiny bridge into muddy grass pocked with hoof-prints, round a bleating sea of soiled white backs, scale three stiles and enter a walled lane where one by one hooded forms are looming through fog. I step aside, out of respect. When the procession has passed and the lane is mist again, I tuck my basket of bread under one arm, gather up my habit, and walk on. As I start down the scree that leads to the Abbey, love streams over my wimple like rain, and I thank the Lord Jesus, who has given us shoes.

From Asylum: Improvisations on John Clare (Pitt, 2019)

The Discovery

On walking, in my seventies, down a leafy street

behind two women in their forties who

are chatting to each other as companionably

as birds on a limb, and having thought, with

happy anticipation, ah, I'll be their age soon!

it occurs to me that I've lost my mind⏤but

just then the cloudsevanesce and light pours

through the oaks and ash, to form lace on

the pavement lovely enough to be sewn

into dresses, and I see that time as as

random as the patterns the sun makes on

any given day as it filters through leaves,

ans as illusory as a baby being born, and

as strange as the years of our lives that

go by without returning, and as equal as

the one friend's auburn hair and the red leaf

she stepps over, which the wind has abandoned

for love of her. and now, having finally

seen that the world is every minute new,

I realize that I'm only a little younger than

those women after all, and I step between

them, and we speak as we walk, and by

the time we part, each of us in her own way

has told the others how lucky she is,

to have been alive in such a beautiful place.

From Homelight, Charlotte Lit, 2023

Mason Bee

-Osmia lignaria

Mason bees live solitarily. Some subspecies have unusual habits, such as lining their nest cavities with flower petals.

Like a religious

you stack your egg in reeds

and seal each chamber

with a dome of clay.

An Indian in a hat

stands in the wind;

his lips are pressed to

a bamboo flute.

He is calling the hums

inside his heart.

He is calling his bees.